From mining to recycling, map the global journey of a Lithium-Ion Battery. Understand how the complex LIB supply chain works and why transparency is vital.

A battery is not just a single object; it is the result of a global engineering effort involving mining, refining, and manufacturing. While most of us only see the final “battery pack,” every single cell inside it is made of components sourced from all over the world. This supply chain is not a simple straight line; it is a complex web. Understanding this web is the first step toward solving the transparency challenges of our future.

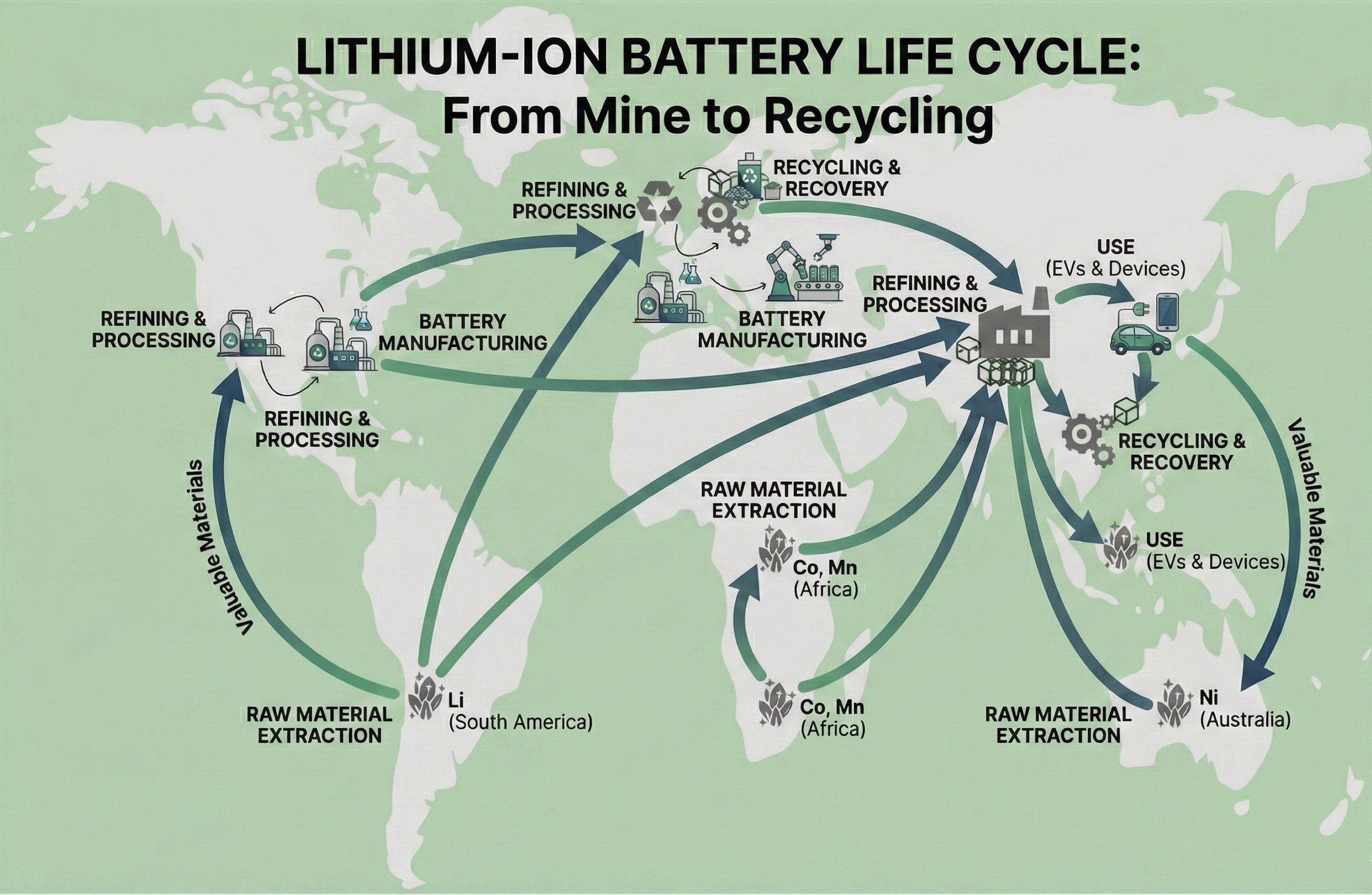

The journey begins deep in the earth with the extraction of the “Big Five” elements: Lithium, Cobalt, Nickel, Manganese, and Graphite. These raw materials are rarely found where the batteries are ultimately manufactured, creating a massive logistical footprint from day one. For instance, about 60% of the world’s Lithium resources are concentrated in the “Lithium Triangle” of South America (Argentina, Chile, and Bolivia) and in Australia [1] . The situation is even more concentrated for Cobalt, a critical element for energy density. Approximately two-thirds of the world’s Cobalt supply originates from a single region, the Democratic Republic of Congo [1] . Meanwhile, the Graphite used for anodes is primarily sourced from mines in China, Brazil, and Canada. This uneven geographical distribution creates inherent risks and dependencies before a single component is even fabricated.

Once extracted, these raw ores must be transported to chemical plants to be refined into high-purity salts. These salts are the building blocks for the battery’s internal architecture: the cathode, anode, electrolyte, and separator. The cathode, housing valuable metals like Nickel and Cobalt, determines the battery’s capacity, while the anode stores the energy. Separating them is a safety layer that prevents short circuits, while the electrolyte acts as the medium for ion movement. The key takeaway here is not just the chemistry, but the logistics: materials mined in one continent are often refined in another, only to be shipped to a third for final assembly.

The transformation of these refined chemicals into a functioning cell takes place in massive facilities known as Gigafactories. The manufacturing process is a feat of precision engineering where these active materials are processed, coated, and assembled into cells. Whether these cells end up in a smartphone or an energy grid, the process requires absolute purity. Any impurity introduced during the long journey from the mine to the factory floor can lead to failure, making the traceability of these materials paramount.

In a traditional linear economy, the story would end when the battery leaves the factory. But in the emerging circular economy, the end of a battery’s life is merely a new beginning. With millions of tons of end-of-life batteries expected to be generated by 2030, recycling has become a critical necessity rather than an option [1] . Valuable metals like Cobalt and Nickel can be recovered through complex industrial processes and reintroduced into the supply chain. This is where advanced technologies become vital; managing this circular flow requires rigorous tracking. As noted in recent research on renewable energy integration, digital innovations like blockchain technology can play a crucial role in ensuring the transparency and traceability of these materials, verifying that waste is managed responsibly and resources are efficiently reused [2] .

We have now traced the path of a Lithium atom from a salt flat in South America to a chemical plant in Asia, through a cell factory, and potentially back into the supply chain through recycling. This journey involves dozens of companies, crosses multiple borders, and navigates various regulatory environments. As supply chains become more complex, tracking the “truth” of a battery becomes nearly impossible with traditional methods [2] . How do we ensure the Cobalt used was ethically sourced? How do we verify the recycled content claims? The system works, but its opacity presents a hidden risk. In our next post, we will explore how to mitigate these risks by potentially using blockchain technology and discuss how we can illuminate the dark spots of this global network.